Ghost spaces of Belgrade

Authors: Predrag Marković & Milica Pajkić

THE ABANDONED ONES

Recent studies in architectural discourse, influenced by globalization, information and capital, indicate appearance of different urban paradoxes and programmatic mutations. These severe historical shifts turned out to be crucial for future development and highly consequent for city’s urban fabric. These complete ideological changes left behind spatial layers of mixed authoritative decisions, symbolical metaphors, social expectations and unfulfilled hopes. In these processes many neglected architectural and urban tissue can be singled out that we recognize and title abandoned spaces.

In our previous analyses we have observed that the term itself is in dialectical sense close to Marc Augé’s term of ‘’non-place‘’ mostly because of that negative attitude towards the character of space. While Augé considers non-places as “buildings and infrastructure necessary for accelerated circulation of people and goods”(Ože, 2005, pp.36), we think of abandoned/ ghost spaces as artificially altered territories which were in some point of time, for some reason abandoned and functionally blank, publicly neglected and left behind to become black holes of its urban context. We find that spaces with lack of integrity and identity, built or unfinished, previously consumed or functionally virginal, all fill the discourse of ”abandoned spaces/places’’, which is essentially quite different from Augé’s ‘’non-place’’. As we see it, ”ghost” is a space inside city’s urban fabric that stands unfamiliar, unfinished, neglected, disconnected, often due to its overall emptiness invisible to the city and its people. In other words, we can say that ghost spaces are architectural orphans of transitions (political, economical, social…etc.). Most importantly, they stand disconnected in people’s recognition of the city although they often have very rich history.

As parts of, by some authors ‘’super-modern’’ city of present, these ghost spaces represent sophisticated forms of architectural disappearance, that urge to be investigated within architectural theory. In terms of local context, Belgrade in the last century went through very dramatical changes- including great political, social, economic and cultural shifts that followed city’s turbulent history. We came to conclusion that the issue of abandoned architecture is active but really neglected. Visibility of this problem was brought through public debates that were organized for this purpose. (Failed Architecture, held on 6 April 2012. at the Cultural City Centre. Before it several conference were organized, like Dictionary of Urban Dilemma and Dictionary of urban solutions, and debate Who builds the city? in Cultural Center REX in Belgrade, oriented and dealing with process of privatization and repurposing of buildings. As a result of these events, “Public Open Spaces” is published this year by the Civic Initiatives.).

There are numerous examples (Photo 1) of this architecture in Belgrade: Building of State printing office “BIGZ”, Power plant “Power and light” (also known as Old Central), Cinema “Slavica”, Building of Old mill, “Rad” office building, Museum of Revolution, New Belgrade’s public garages, “Beko” building, Old Fairground, Shopping mall “Konjarnik”, Cotton combine, territory of Sava’s amphitheatre, etc. Although there were some efforts towards dealing with this problem of devastated and abandoned architecture, it seems like until now there are little results.

Abandoned public garage on New Belgrade

ARCHITECTURE OF NO PROGRAMME

In contemporary world, process of globalization, which was made by developed capitalistic society in order to negate stability and autonomy of identity, brought the fascination with abstraction, disappearance, over presence and availability. In that sense, abandoned/ghost spaces, non-places, and other similar phenomena are easily identified ‘’as typical expressions of the age of globalization’’ (Ibelings, 2003, pp. 66). Inexistence of identity, absence of function and meaning, lack of liaisons with surrounding characterizes architecture of no programme. Causes of their existence often lay in failed concepts, political, economical and cultural breakdowns that affect all structures and layers of society’s actions, especially architecture, as highly dependent discipline. One of the most recognizable characteristics of abandoned space is the absence of content, activity and program. Object without program represents just a simple shell. If we follow Bernard Tschumi’s premise that ‘’there is no architecture without program, without action, without event’’ (Tschumi, 2004, pp.11) our recognized abandoned spaces represent unique, ambivalent architectural act. They are not solely present in Belgrade, but seem to be an emerging phenomenon throughout developed countries of both the East and West.

The other coherent characteristic is by time beginning to appear- the aesthetic of decadence. Marked by solitude of architecture without everyday life and maintenance, emptiness, wracked glass, broken concrete, peeling paint, demolished glass and sometimes water and fire scars.

Essential elements for city’s re-appropriation and reanimation of those lost spaces firstly depend of the state of the architectural object, human perception of it and its capabilities and capacity for re-programme the existing. Those re-birth demand creative approaches and strategies for graduate transformation and comprehension of this abandoned architecture into the active, live network of the city.

Another relation, important for understanding of an abandoned space is the global phenomena of mass production and consumption of content. The basis of current value-system, manner of living and thinking is economy. French philosopher Nicolas Bourriaud noticed that the “consumption is a mode of production…consumption creates the need for new production, consumption is both its motor and motive” (Bourriaud, 2007, pp.22). Constant economic growth creates stability that makes architecture flourish and develop but also on the other side the dependence of architecture on economy makes it more vulnerable to financial shocks. Accordingly, Yugoslavia was for some time part of the developed world, but its internal conflicts led to economical instability and eventually total breakdown, which resulted with numerous urban and architectural failures. Augé notices the same: “Countries of Eastern Europe kept their exotic authenticity because they have no means to join world’s consumption space” (Ože, 2005, pp.101).

THE BURDEN OF MODERNIZATION…

During the 20th century, Belgrade experienced several radical shifts of country’s political course, as it is presented in introduction of this paper. That indirectly caused discontinuity in urban development and degradation of initiated projects. Counting only the period of last hundred years, Belgrade was capital of eight different countries (Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918-1929.), Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941.), Democratic Federal Yugoslavia (1945.), Federal Public Republic of Yugoslavia (1945-1963.), Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963-1992.), Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1992-2003.), Serbia and Montenegro (2003-2006), Republic of Serbia (2006- )).

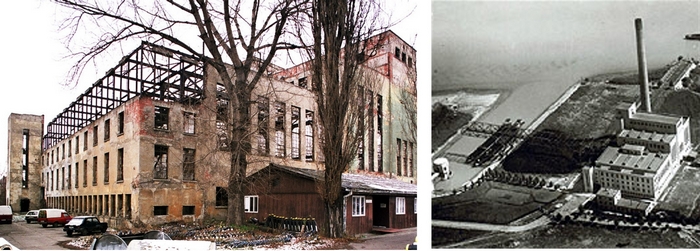

In light of those many periods, it seems that that first projects interesting for their abandonment are industrial ones. Belgrade was among few European cities that, by the end of 19th century, introduced electrical power. Due to industrialization of the city, the country was drawn by modernization. This was important because it brought new social layers, development of transport and telecommunications, and mostly, general cultural progress. One of this kind of projects is the power plant “Power and light” in Belgrade. It is situated in old city centre, Dorćol, near right riverside of Danube. Project represented the great power of country (at that time Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941.)) that tended to be technologically advanced, at the end of 19th and beginning of the 20th century, by introducing AC.

Life for this architectural artefact began in 1929. when the Commission members of the Municipality of Belgrade decided to build a power plant through an architectural competition in which 14 foreign and 2 Yugoslav companies participated. After only two years of construction, in 1933. Power plant began to work and it was in property of Municipality of Belgrade city.

The architecture of the building was based on modularity, and four production units were constructed, latest in 1938. Form of the building adopted relatively new Bauhaus aesthetics that was marked by the absence of ornamentation and harmony between the function of an object and its design, unifying art, craft, and technology. In 1947. power plant “Power and light” by nationalization process was transferred into state ownership. Unfortunately Plant worked until 1967. when the technology changed and it was necessary to shift to fuel oil. It stopped working in 1969. Once more political, ideological and economic changes of the Federal Public Republic of Yugoslavia have affected on architecture. Ever since, it was exposed to a constant decadence and neglecting.

Power and light, today and before

Although it seems that the main reason of its abandonment wasn’t economy, yet a need for new technological advances, it is clear that during the process of overall metropolization of Belgrade,

it could not contribute sufficiently. Today, all that is left is the main building (Photo 2), water pump, crane and filter plant. This is an ideal condition for project reprogramming, because it is a true ghost space without memories, ready for new ones to be made. In today’s sense, industrial heritage, in addition to be important part of urban and architectural tissue, is a specific part of city’s culture. Because of this, it is of great importance to infiltrate and re-programme this kind of buildings in new historical, social and economic aspects of contemporary life, as to create place for urban pop culture to develop.

THE BURDEN OF GLOBALISM

As of economy of Yugoslavia, it went from glorious results in mid-60s and 70s to absolute breakdown during the 90s. We have already determined that abandoned spaces are spatial residues of fundamental societal changes as in the first example, but in the case of Belgrade, we can mark the year 1980. as the starting point of their formation within the city. That was the year in which complex system of governance started to collapse, among other causes following the death of country’s lifetime leader and president, Josip Broz Tito. The former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia that was formed in 1963. was breaking down, and finally dissolved in 1992. which caused enormous problems in all fields of life.

In the 70s the change was primarily shifted on the international architectural scene, because of new architectural aesthetic of postmodernism. This is the period of false economic prosperity of Yugoslavia, based on a number of foreign borrowings, in which one can search for the first conditions for formation of abandoned architectural spaces.

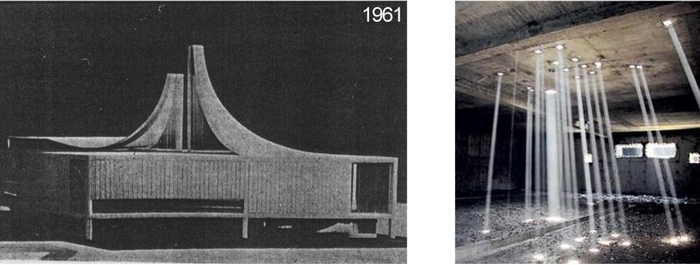

Accordingly, “monument wants to be perceptible expression of eternity” (Ože, 2005, pp. 58). Also, eternity is ultimate dream of every kind of power or government. Exactly the same was the need of communist government in Yugoslavia after the War. In urgent need to reconstruct past and deconstruct reality, glorifying appropriate, ideologically acceptable moments and personalities, in 1959. institution of Museum of Revolution of the Peoples and Ethnicities of Yugoslavia was formed. After the competition in 1961., project of architect Vjenčeslav Rihter was selected for realization. But the period between selection of project and beginning of actual construction made it meaningless. Time gap of nearly 20 years of preparation of the project, administration’s uncertainty, changes of location and shifts of whole ideological context made the Museum lost both in space and time. It’s construction finally begun in 1978. but was soon ended, leaving only the basement level and ground-floor slab finished.

But “if finished, it would have been a white box raised on large-span columns, topped by a dynamic sculptural skylight… But despite this formal similarity with the rest of New Belgrade, the design of the Revolution Museum was a result of significantly different motivations and theories about the role of architecture in a socialist society and about the appropriate architectural representation of the country” (Kulić, 2009, 305). This example of an aesthetic of decadence is a true mark of wandering political ideology that often changed its priorities and fields of interest, leaving them half-finished. And quite an irony it produced, unfinished Museum of Revolution (people’s, communist, for freedom and equality) is at this moment shelter for several homeless people and there are some propositions that in future it could become the foundation of Belgrade Opera house. Communist ideology, misery and bourgeois culture, they all meet at this place.

Ideology of equality, harsh realism and bourgeois dreams meet at the same place

ECONOMY STRIKES YET AGAIN

Last period covered by this analysis is the transition period, after the War and the disintegration of former Yugoslavia during the nineties and important political changes in Serbia, after 2000. Like Miloš R. Perović said, the most significant change in Serbian architecture of the past decades of twentieth century was the changing attitude towards money, with the building became the subject of a market (Perović, 2003). It is clear that one of the biggest influences on architecture was pursued by economy. The consequence was obvious. The half ruined aesthetic of the city- wracked glass, broken naked concrete walls and abandoned spaces were numbering up.

One of the most evident examples of architectural dependency to stability of economy is a true abandoned place, office building of one of the most successful Yugoslavian construction companies, GP ‘’Rad’’. Construction begun in 1989. But, due to numerous problems, mostly financial, works stopped in 1998, when building was almost 90% finished. Since then, nearly 60.000 square meters of offices, congress centre and retail space have been left in silence. The company bankrupted, and the faith of the whole project was sealed.

One of the best postmodern examples of Serbian architecture sinks into oblivion

This building represents the perfect intersection of several paradigms and influences in recent Belgrade’s history that led directly to formation of abandoned architecture: collapsed economy, disoriented politics, and loss of social and cultural compass. Although located in the very centre of today’s business district of New Belgrade, Rad’s building is literally invisible. This invisibility comes as a direct consequence of space’s numbness, lack of content that would attract activities and people, and bring building, as architectural act, back to the mental map of people and urban fabric that surrounds it.

THE CULMINATION – “BIGZ” STATE PRINTING COMPANY

Surely, one of the most media talked-about objects in Belgrade that we recognized as an example of abandoned architecture of the city is the “BIGZ” (Photo 3). At the time the main objective of the architect Dragiša Brašovan was to design a form that is in shape of Cyrillic letter “П”, and symbolized a printing machine. Today, this project is one of the main examples of Yugoslavia’s architectural modern movement. It was constructed in Senjak between 1937. and 1943, covering more than 25 000 square meters. At the time it was in property of the country and had more than 3000 employees. In the year 1992. the building was put under the protection of City Department for the Protection of monuments of culture, which relates to its important role in architectural heritage. But also, these 1990’s were crucial for its transformation into an abandoned one. Firstly, because of the disintegration of former Yugoslavia that began in 1991. and secondly, economic enervation that was followed by decadence of the most firms that were in public property. In the years of transition, after 2000. it was, like many, in process of privatization.

Today, this icon of Belgrade’s modern architecture (in which some recognize the elements of Bauhaus) turns into an immense quantity of dirty concrete, wracked glass, more than 10 000 square meters of dark hallways, on which the traces of time, absence of use and lack of recourses are more than visible.

Through previous analyses we have jet recognized this architectural artifact also as positive example. In last several years, mainly owing to economic aspect, the Graphics company “BIGZ”, which is the majority owner of the building (about 80%), leased 5000 square meters on second, sixth and seventh floor of the building. During the time, space was spontaneously filled with various artists that created workshops, clubs and places of creation. This is where aspect of economy demonstrates its great power: a paradox – a force that once destroyed a great architectural piece of modern, was capable to transform it in rare informal cultural center of Belgrade’s underground life. But the question remains, is it capable once more to overcome this situation, and let Brašovan’s architecture to be converted into a hotel or business center? Some speculation exists.

BIGZ, monument of Serbian modern architecture, symbol of hope for other ghost spaces

HEALING THE ABANDONENCE

Privatization of old buildings, their re-appropriation or total devastation could have serious consequences for the urban fabric of the city. It could lose the points of its normal functioning and at the end its profit. Additionally, through improper urban and architectural tools, the users loose attachment to a place and it soon becomes abandoned, the infected tissue of the city. These processes may therefore have deleterious consequences regarding public importance. The lack of uniform and clearly defined cultural policy that would provide the necessary real purpose of these facilities has resulted with only temporary solutions. It seems that the adoption of master plans, as far as it is good for planning of the future development of the city, neglects individual problems-microstructures.

Because of the severe financial crisis, all of sudden, sites were abandoned, leaving nearly finished structures to the temper of time. By definition, they are neglected, but their uniqueness is hidden in their temporary alternative functionality, which manifests thanks to institutional chaos and potential of its aesthetics of decadence. Overall legal vacuum in whole country provides the opportunity to host paintball sessions, kart races, and other easily replaceable programs. Exactly this type of relation between space and program could assist in finding suitable methodology in reviving of these spaces.

But the question remains- what the true re-programming process includes? Although it could not be easily defined because of the nature and history of each individual abandoned building we could offer some directions. It seems that it involves all three main factors: the history of abandonment, aesthetics of decadence and economy. The first, deals with the past- analysing reasons of emptiness, stage of its ruins and former programmes. The second one deals with present in that manner that it tries to reoccupy decaying by reversing it. Nevertheless, simple renovation, reuse or renaissance does not respect the burden of time and importance of history that this aesthetics embodies and which must be interpreted into the new. But very often third factor economy- which is in this globalised consumer world the important one faced to future- lacks a respect for decay. In this absence lies the very problem of re-programming. In order to re- programme the architecture of abandoned places in Belgrade actions must be: inclined to accept the aesthetics of decadence, to recognize its positive stances and to transform them in accordance to their history and through economy into a vivid architecture programme- in such way that the project stays intertwined with its surroundings. Because of this we conclude with Hans Ibelings statement that ‘’the new frame of reference will no longer be dictated by the unique, the authentic or the specific, but by the universal.’’ (Ibelings, 2003, pp.135).

It seems that young artists and organizations made the first effort of re-programming in architecture. One of the most obvious proofs of this is the Mikser festival held from 2010. in place of old industrial complex on the Danube waterfront “Zitomlin”. Introducing art into the old architectural membrane has re-programmed this space for new facilities in accordance with modern times. Last session of Mikser was held in Sava mala, an old, neglected quarter of city centre, marking not just one object, but whole area as a valuable yet decaying neighbourhood, which was by that time slowly turning into an abandoned place. The approach of Mikser’s organizers could become one direction in which possible strategies of development and rebirth of ghost spaces might evolve. Its main features are minimal investments into the contents, absence of physical changes in space but as it is a temporary type of program, but its lifetime is too short to fully reprogramme an abandoned space. The series of manifestations with similar approach, hosted in those identified ghost spaces could gradually lead to their re-appearance on cultural map of the city and slowly lead them towards the complete integration into the city’s urban life.

Maybe the most obvious example of revival of a ghost space in Belgrade is “Beton Hala” Waterfront centre. At first, artists and club renters came to old hangars. Soon this location became one of the most visited places of Belgrade’s underground scene. Old space with is concrete aesthetics and strait lines of architectural form gathered artists, musicians, architects, designers and lovers of nightlife. Once an abandoned space turned out to be a place to be seen. But hidden, there is a logical explanation that lies in economy. Firstly, this is one of the most expensive city’s locations where prices of rent are very high but could be paid through catering. This is animated more with nearness of rivers and its developed tourism. Secondly, city built a garage just above this place, and made additional revenues. This confirms Tschumi’s statement that ” programs have long since ceased to be determinative, because the constantly changing – the design of the building, during construction and, of course, after he finished” (Tschumi, 2004, pp.93).

As a contrast to “Power and light” object we could here analyse the effectual re-programming strategy of one more industrial object- the old warehouse that was built in 1884. in Old Belgrade’s city centre near Sava river. Cultural Centre Grad (Photo 4), formed in 2009. on the initiative of Cultural Front Belgrade and Felix Meritis foundation Amsterdam today become the place of cultural events. This multifunctional space restored the atmosphere of old building, adding only the necessary, jet recycled furniture. In keeping the original architecture as only a shell and adding simple new programme for turning into a cultural centre, Grad has enabled organization of programs such as exhibitions, concerts, debates, performances, conferences and workshops, etc…

Mixer Festival, a possible way to revive abandoned spaces

HOW TO REPROGRAMME?

Starting with the fact that although abandoned architecture once was the node (one of five Lynch’s elements of a city), today it is totally disconnected from city’s vibe. But let’s not forget that, Lynch (1960, 72) distinguishes two types of nodes in his Image of the city– those that are at major intersections, and those that are characterised by concentration with a thematic activity. While in most cases life of the city has shifted in other locations and districts, thematic activity could easily be created with a new programme. As to the aesthetic of decadence typical strategies for these abandoned buildings (most commonly: demolition, renovation, replacement, or continued neglect) do not achieve the proper goal and in some cases do not take the existing aesthetic into account. Demolition removes all traces of the previous, renovation often needs a new disposition, replacement brings totally new and erases previous history and affects on people’s memories of a place, and at the end continued neglect causes just more problems and urban confusion.

As seen in these few examples, in last 30 years, various influences conditioned formation of architecture of no programme in Belgrade. While the political situation nowadays is relatively calm, economical, social and cultural problems are piling up and risking increase of neglected, forgotten spaces within the city. In order to make a complete transformation, these spaces must gain some purpose, which could justify their further existence and prove their value in contemporary city. As Nicolas Bourriaud states “appropriation is indeed the first stage of postproduction” (Bourriaud, 2007, pp.25). The conclusion is that the biggest cause of this, in addition to permanent social, ideological and cultural policy of the state, is the economy. Insufficient recourses, which were boosted by the recent economic crisis on the global level, and a lack of good long-term programs and tools for maintenance and re-appropriation of these facilities leads to their spontaneous transformation into the abandoned ones.

In the same context, eventual bringing back to life of an abandoned space would represent a new mode of production, or because it operates with something existing, architectural version of postproduction. As we have presented here, industrial object could become a fertile terrain for various strategies of re-programming the architecture. Firstly, because of the huge opened space, and secondly, because of its prospects in new raw design tendencies. However, it is necessary to restore and maintain constant dialogue between specialists – leading thinkers, architects, urban planners, economists, etc. for the activation of these facilities.

Rescheduling the abandoned space plan is required and also the willingness of architecture to be flexible, amorphous and unstable. But the process of re-programming of these spaces is not solely the act of architecture. It firstly includes re-programming in urbanism, with renewed spatial plans in order to link this objects within city’s net and to form a specific, well-organized tissue. New strategies that include stable economy plans, cultural events that are sometimes drawn by the history of place (like with Power and Light power plant and Bigz) are also crucial for activity and bringing back these kinds of places into a global reality. By adding new contents to abandoned ghost spaces they will bring back the old memories, but at the same time will create new. Regaining attractiveness they will lose their “ghosts”.

By following today’s trend in creating an Architecture policy (kind an informal document of state and future of architecture of the country and its regions) Serbia should formulate important principles and contain directives for short and long-term actions. First step should be a better understanding of the present state in the field of architecture and urban planning, followed by public discussion that includes architect, politicians, general public and all involved parties, taking into account experiences of implementations. Afterwards particular part of AP should be developed in coordination with local administrations, professional organizations, government and non-government departments and organizations in order to achieve broad consensus on this question. This way abandoned architecture and its aesthetic could find needs and way to be reprogrammed in multilayered discourse of present architecture. Regarding abandoned ones, the general and primary intention of the architectural policy should be to promote programme and re-programme, to evaluate the state of decadence and context, the quality of the planning and construction of buildings, in which the concept of “quality” cannot be defined as one particular attitude to architecture and its surroundings, but rather as a mindset and a more complex approach to spatial development.

REFERENCES:

Blagojević, Lj. (2011). Postmodernism in Belgrade architecture: Between cultural modernity and societal modernization, Spatium Internation Review, No.25, pp. 23-29.

Bourriaud, N. (2007). Postproduction. 3rd edition. Berlin-New York:Lukas & Sternberg.

Fein, E.Z.( 2011). The Aesthetic of Decay: Space, Time, and Perception.[online] Available at: zfein.com/architecture/thesis/thesis.pdf [Accessed 17 September 2013].

Ibelings, H. (2003). Supermodernism: Architecture in the age of globalization. Rotterdam:NAI Publishers.

Jankov, Sonja (2012). (Javni) prostori Beograda. B92.net.[online] Available at: <http://www.b92.net/ kultura/ moj_ugao.php?nav_category=1086&yyyy=2012&mm=06& nav_id=616095>[Accessed 20 July 2012].

Kulić, V. and Mrduljaš, M. (2012). Modernism in-between : the mediatory architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia. Berlin: Jovis.

Kultermann,U. (1980). Architecture in the seventies. London : The Architectural Press.

Ože, M. (2005). Nemesta: Uvod u antropologiju nadmodernosti. Beograd:Biblioteka XX vek.

Linč, K. (1974). Slika jednog grada. Beograd: Građevinska knjiga.

Perović, M. R. (2003). Srpska arhitektura XX veka: od istoricizma do drugog modernizma. Beograd: Arhitektonski fakultet.

Tschumi, B. (2004). Arhitektura i disjunkcija. Zagreb: AGM.

PHOTOS REFERENCES:

Photo 1- image by the authors

Photo 2- http://bif.rs/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/snaga-i-svetlost.jpg

Photo 3- http://farm7.staticflickr.com/6014/6004182161_a4918477d8_z.jpg

Photo 4- http://stillinbelgrade.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/grad1.jpg

Photo 5- http://www.pravda.rs/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/kc-grad-fasada.jpg